The Politics of SCOTUS’ Leaked Abortion Opinion

May 17, 2022

United States Supreme Court Justices are not supposed to be political, but there is a form of politics that takes place on most controversial cases. The leaked opinion in the pending abortion case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, gives us a peek into the Supreme Court’s politics.

There can be little doubt that Roe v. Wade and even Planned Parenthood v. Casey were political decisions, not legal judgments. Alito’s draft opinion makes that clear. So, I suspect it was easy for at least five Justices to decide in favor of upholding the constitutionality of the Mississippi law prohibiting doctors from performing abortions at 15 weeks.

The trickier part was the holding. Should affirmation of the enforceability of the Mississippi law include the reversal of Roe and Casey?

When the Chief Justice is among the majority in favor of a decision, he has the prerogative to write the opinion or assign it to a justice of his choosing. That Roberts did not write the draft opinion indicates either the holding he wanted or the reasons he wanted to give for his preferred holding would not garner the support of at least four more of his colleagues (five being needed).

Apparently, a majority wanted to reverse Roe and Casey and, therefore, there was no one in the majority to whom Roberts could assign the opinion; he was a minority of one! Everyone knew the other three justices would uphold those decisions.

When the Chief is not among the majority, the next most senior justice who is in the majority can write the opinion or assign it to another justice. That would be Justice Clarence Thomas.

Thomas has made it clear he thinks Roe and Casey were wrongly decided, but he also thinks the Court’s made-up doctrine of substantive due process, its view of stare decisis (how to deal with precedent) are wrong and unconstitutional. But Thomas had to know that what he would want to write on those two subjects would not get the votes of the other four justices who wanted to reverse Roe and Casey. His views would be “too extreme” either for their political tastes or too debilitating to their more expansive understanding of the judicial power.

Justice Alito was Thomas’ choice. Presumably Thomas thought Alito could dismantle Roe in an opinion that could garner the support of Kavanaugh and Barrett. But Thomas also thought Alito could write an opinion with enough sections and subsections dealing with particular topics that Thomas could refuse to join and into which he could throw serious punches at substantive due process and stare decisis.

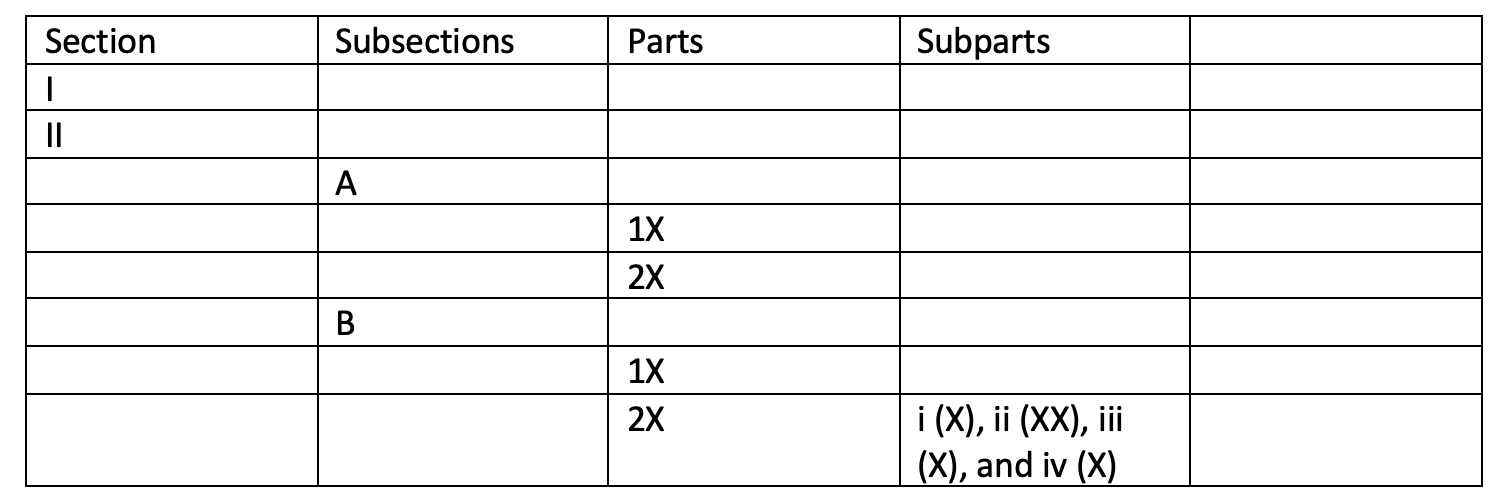

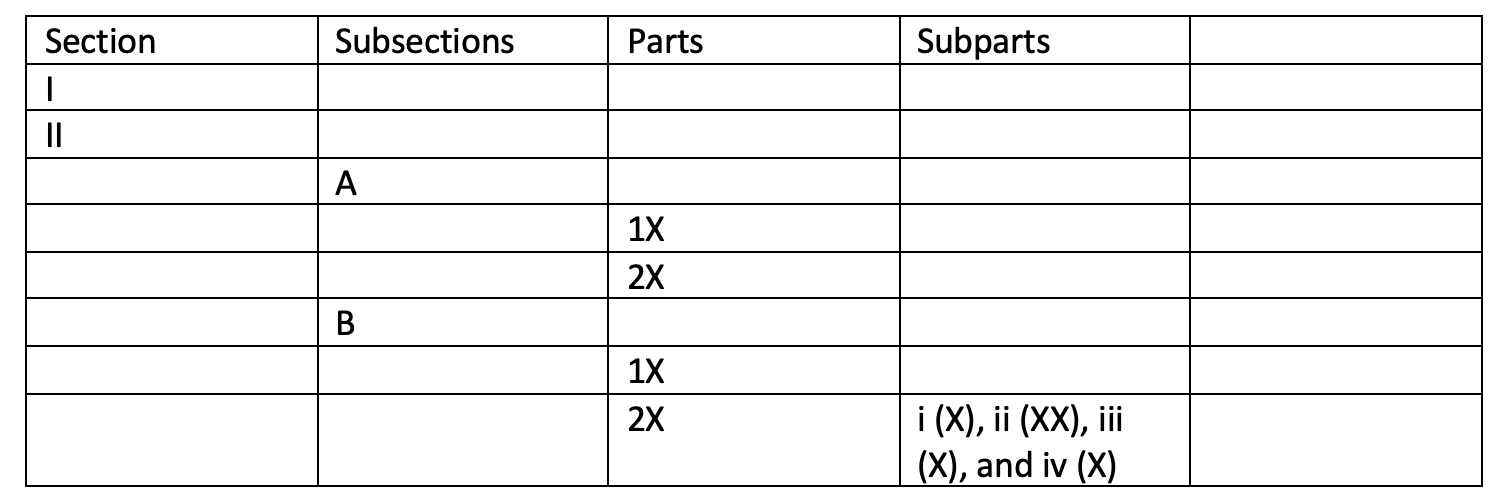

Maybe this will demonstrate what I mean. In Alito’s draft opinion there is an introduction and then six sections, I-VI. I will only highlight Sections I and Section II. Section I has no subsections. But Section II is broken down into two subsections, and several parts, and subparts as demonstrated in the graphic below.

As you can see, there are a lot of “moving parts” in Alito’s draft opinion and each “X” represents a part of the opinion a justice can agree or disagree with. In each instance a justice can add atweak to the given explanation or criticize it.

The most glaring sign of politics is found in the Court’s treatment of stare decisis. As I read the opinion and the analysis employed by Alito, I thought he was also sounding the death knell for its 2015 same-sex “marriage” decision, returning the issue of marriage and family law back to the states.

The critique he applied to abortion and its relationship to common law applied with equal force of logic to same-sex“marriage.” By parity of reason, a right to a marital relation defined in terms of two men or two women could not be any more rooted in the common law than abortion.

But Alito’s opinion sought to put a halt to such logical thinkingwith these words: “Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.”

No doubt that makes Kavanaugh or Barrett, or both, happy enough to sign onto parts of Alito’s lengthy opinion. I will bet my bottom dollar (not really) that at least Kavanaugh joins the part of Alito’s opinion where that language is found, and Thomas does not!

Since the Court is only to rule on the issue in front of them, which was whether abortion was a liberty right, it was not necessary for the majority to say what it thought about state marriage laws.

But there was no way for Alito to refute the abortion right without a form of analysis that put same-sex marriage in doubt (or, worse yet for some, declare the unborn “persons” under the 14th Amendment!).

That is why Alito effectively said, “Don’t go there with this opinion despite everything I just said.” What that means is the Court is still playing politics on constitutional issues involving the LGBT community. On their issues, it is Roe-styled politics as usual.

There can be little doubt that Roe v. Wade and even Planned Parenthood v. Casey were political decisions, not legal judgments. Alito’s draft opinion makes that clear. So, I suspect it was easy for at least five Justices to decide in favor of upholding the constitutionality of the Mississippi law prohibiting doctors from performing abortions at 15 weeks.

The trickier part was the holding. Should affirmation of the enforceability of the Mississippi law include the reversal of Roe and Casey?

The First Sign of ‘Politics’—Who Writes the Opinion?

When the Chief Justice is among the majority in favor of a decision, he has the prerogative to write the opinion or assign it to a justice of his choosing. That Roberts did not write the draft opinion indicates either the holding he wanted or the reasons he wanted to give for his preferred holding would not garner the support of at least four more of his colleagues (five being needed).

Apparently, a majority wanted to reverse Roe and Casey and, therefore, there was no one in the majority to whom Roberts could assign the opinion; he was a minority of one! Everyone knew the other three justices would uphold those decisions.

When the Chief is not among the majority, the next most senior justice who is in the majority can write the opinion or assign it to another justice. That would be Justice Clarence Thomas.

Thomas has made it clear he thinks Roe and Casey were wrongly decided, but he also thinks the Court’s made-up doctrine of substantive due process, its view of stare decisis (how to deal with precedent) are wrong and unconstitutional. But Thomas had to know that what he would want to write on those two subjects would not get the votes of the other four justices who wanted to reverse Roe and Casey. His views would be “too extreme” either for their political tastes or too debilitating to their more expansive understanding of the judicial power.

Justice Alito was Thomas’ choice. Presumably Thomas thought Alito could dismantle Roe in an opinion that could garner the support of Kavanaugh and Barrett. But Thomas also thought Alito could write an opinion with enough sections and subsections dealing with particular topics that Thomas could refuse to join and into which he could throw serious punches at substantive due process and stare decisis.

Maybe this will demonstrate what I mean. In Alito’s draft opinion there is an introduction and then six sections, I-VI. I will only highlight Sections I and Section II. Section I has no subsections. But Section II is broken down into two subsections, and several parts, and subparts as demonstrated in the graphic below.

As you can see, there are a lot of “moving parts” in Alito’s draft opinion and each “X” represents a part of the opinion a justice can agree or disagree with. In each instance a justice can add atweak to the given explanation or criticize it.

The Second Sign of Politics—Language to Make Some Justices Happy

The most glaring sign of politics is found in the Court’s treatment of stare decisis. As I read the opinion and the analysis employed by Alito, I thought he was also sounding the death knell for its 2015 same-sex “marriage” decision, returning the issue of marriage and family law back to the states.

The critique he applied to abortion and its relationship to common law applied with equal force of logic to same-sex“marriage.” By parity of reason, a right to a marital relation defined in terms of two men or two women could not be any more rooted in the common law than abortion.

But Alito’s opinion sought to put a halt to such logical thinkingwith these words: “Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.”

No doubt that makes Kavanaugh or Barrett, or both, happy enough to sign onto parts of Alito’s lengthy opinion. I will bet my bottom dollar (not really) that at least Kavanaugh joins the part of Alito’s opinion where that language is found, and Thomas does not!

Since the Court is only to rule on the issue in front of them, which was whether abortion was a liberty right, it was not necessary for the majority to say what it thought about state marriage laws.

But there was no way for Alito to refute the abortion right without a form of analysis that put same-sex marriage in doubt (or, worse yet for some, declare the unborn “persons” under the 14th Amendment!).

That is why Alito effectively said, “Don’t go there with this opinion despite everything I just said.” What that means is the Court is still playing politics on constitutional issues involving the LGBT community. On their issues, it is Roe-styled politics as usual.