Is “Statesman” an Extinct Category in Our Day?

Sep 1, 2022 by David Fowler

Can you think of a person over the last 30 years you would consider a statesman? I would like to think I was one during my 12 years in the Tennessee Senate, but alas, something I read the other day made me realize I did not come close. See if you would agree with my assessment of what a statesman is.

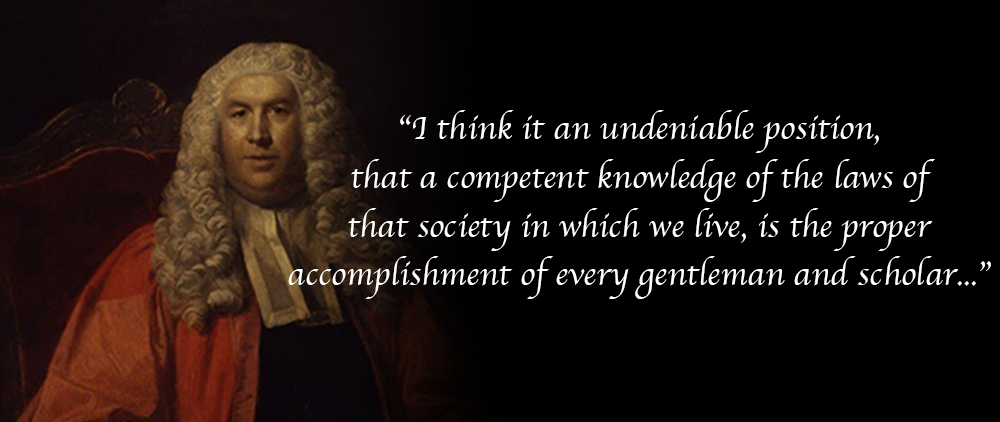

My view of statesmanship was taken to task by these words from William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, first published in 1765. For the most part, it is comprised of his law school lectures. Its continuing importance is demonstrated by the United States Supreme Court citing it approvingly in support of its abortion and Second Amendment decisions this past June.

Blackstone’s discussion of what makes one a statesman begins with this opening observation:

And why is this needed?

In other words, civil liberty[i] is at stake. Therefore, “it is incumbent upon every man to be acquainted with those [laws] at least with which he is immediately concerned; lest he incur the censure, as well as inconvenience, of living in society without knowing the obligations which it lays him under.” (emphasis supplied)

Beyond the general populace, he laid a particular onus on the clergy, “The clergy in particular, besides the common obligations they are under in proportion to their rank and fortune, have also abundant reason, considered merely as clergymen, to be acquainted with many branches of the law.” The reason is simple: law deals with right and wrong, which should be of importance to clergy.

By way of example, I am reading a booklet by George Park Fisher from January 1864, a theologian and historian, entitled Of the Distinction between Natural Rights and Political Rights.[ii]

Then Blackstone proceeds to those “on whom nature and fortune have bestowed more abilities and greater leisure.” These, he says, “cannot be so easily excused” from their knowledge of the law as the general populace. Here is why:

“In the laws” is not referring to a basic civics class, but the law itself, the nature of law and its relation to particular laws.

Do you think the “movers and shakers” in our society have that knowledge?

Finally, he speaks to those “ambitious of representing their country in parliament.” Here is Blackstone’s charge to them regarding their duties and responsibilities, first by way of negation:

Now he charges them by way of affirmative duties:

The United States Constitution today bears no resemblance to what the states adopted. And what would Blackstone say to that:

I suspect Blackstone would say it is “utterly ignorant” that our governor and Republican legislature (and those of more than 30 other states) think and act like the United States Supreme Court can not only redefine marriage but re-write the marriage laws of every state to conform to its new definition.

But here is why I could not have called myself a statesman, not according to Blackstone’s standard, which I believe should be ours, and why I can say I have yet to know one:

I will end with Blackstone’s description of what happens when such instruction and knowledge of the “science of law” is lacking among those whom we elect [iii]:

Mischief is the consequence. I hope I have done my duty as a citizen and former legislator to bring this to the public attention.

[i] Civil liberty is the right to do “what the law permits.” The ignorant of today think it means the law must let them do what they want. That is why liberals hate our common law foundations and the episodic Supreme Court decisions that rest on them.

[ii] The etymology of the word “clerk’ used in government today, e.g. “law clerk” or “Clerk of Court” drives home the close relation between law and the clergy that once existed. “c. 1200, ‘man ordained in the ministry, a priest, an ecclesiastic,’ from Old English cleric and Old French clerc ‘clergyman, priest; scholar, student,’ both from Church Latin clericus ‘a priest,’ noun use of adjective meaning ‘priestly, belonging to the clerus’.”

[iii] Some think they would qualify because they went to law school. I am proof a legal education is not sufficient to qualify as a statesman. For example, most, like me, think common law is judge made law, because that is what most law students have been taught for over 80 years. That belief is a modern innovation arising from an evolutionary worldview, not a Christian one.

David Fowler served in the Tennessee state Senate for 12 years before joining FACT as President in 2006.

My view of statesmanship was taken to task by these words from William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, first published in 1765. For the most part, it is comprised of his law school lectures. Its continuing importance is demonstrated by the United States Supreme Court citing it approvingly in support of its abortion and Second Amendment decisions this past June.

What the Populace Needs to Know to Identify a Statesman

Blackstone’s discussion of what makes one a statesman begins with this opening observation:

I think it an undeniable position, that a competent knowledge of the laws of that society in which we live, is the proper accomplishment of every gentleman and scholar; a highly useful, I had almost said essential, part of liberal and polite education.

And why is this needed?

[T]o demonstrate the utility of some acquaintance with the laws of the land, let us only reflect a moment on the singular frame and polity of that land which is governed by this system of laws. A land, perhaps, the only one in the universe, in which political or civil liberty is the very end and scope of the constitution.

In other words, civil liberty[i] is at stake. Therefore, “it is incumbent upon every man to be acquainted with those [laws] at least with which he is immediately concerned; lest he incur the censure, as well as inconvenience, of living in society without knowing the obligations which it lays him under.” (emphasis supplied)

The Role of Clergy in Helping the Populace Identify a Statesman

Beyond the general populace, he laid a particular onus on the clergy, “The clergy in particular, besides the common obligations they are under in proportion to their rank and fortune, have also abundant reason, considered merely as clergymen, to be acquainted with many branches of the law.” The reason is simple: law deals with right and wrong, which should be of importance to clergy.

By way of example, I am reading a booklet by George Park Fisher from January 1864, a theologian and historian, entitled Of the Distinction between Natural Rights and Political Rights.[ii]

The Obligation of Society’s Leaders

Then Blackstone proceeds to those “on whom nature and fortune have bestowed more abilities and greater leisure.” These, he says, “cannot be so easily excused” from their knowledge of the law as the general populace. Here is why:

These advantages are given them, not for the benefit of themselves only, but also of the public: and yet they cannot, in any scene of life, discharge properly their duty either to the public or themselves, without some degree of knowledge in the laws. (emphasis added).

“In the laws” is not referring to a basic civics class, but the law itself, the nature of law and its relation to particular laws.

Do you think the “movers and shakers” in our society have that knowledge?

The Statesman’s TWO-FOLD ‘Job’

Finally, he speaks to those “ambitious of representing their country in parliament.” Here is Blackstone’s charge to them regarding their duties and responsibilities, first by way of negation:

[T]hose, who are ambitious of receiving so high a trust, would also do well to remember its nature and importance. They are not thus honourably distinguished from the rest of their fellow-subjects, merely that they may privilege their persons, their estates, or their domestics; that they may list under party banners; may grant or withhold supplies; may vote with or vote against a popular or unpopular administration; but upon considerations far more interesting and important.

Now he charges them by way of affirmative duties:

They are the guardians of the English constitution; the makers, repealers, and interpreters of the English laws; delegated to watch, to check, and to avert every dangerous innovation, to propose, to adopt, and to cherish any solid and well-weighed improvement; bound by every tie of nature, of honour, and of religion, to transmit that constitution and those laws to posterity, amended if possible, at least without any derogation. (emphasis added)

The United States Constitution today bears no resemblance to what the states adopted. And what would Blackstone say to that:

And how unbecoming must it appear in a member of the legislature to vote for a new law, who is utterly ignorant of the old! what kind of interpretation can he be enabled to give, who is a stranger to the text upon which he comments!

I suspect Blackstone would say it is “utterly ignorant” that our governor and Republican legislature (and those of more than 30 other states) think and act like the United States Supreme Court can not only redefine marriage but re-write the marriage laws of every state to conform to its new definition.

Why There Are No More Statesmen

But here is why I could not have called myself a statesman, not according to Blackstone’s standard, which I believe should be ours, and why I can say I have yet to know one:

Indeed it is perfectly amazing that there should be no other state of life, no other occupation, art, or science, in which some method of instruction is not looked upon as requisite, except only the science of legislation, the noblest and most difficult of any.

Apprenticeships are held necessary to almost every art, commercial or mechanical: a long course of reading and study must form the divine, the physician, and the practical professor of the laws; but every man of superior fortune thinks himself born a legislator.

Yet [Cicero] was of a different opinion: “It is necessary,” says he, “for a [Roman] senator to be thoroughly acquainted with the constitution; and this,” he declares, “is a knowledge of the most extensive nature; a matter of science, of diligence, of reflection; without which no senator can possibly be fit for his office.” (emphasis added).

Apprenticeships are held necessary to almost every art, commercial or mechanical: a long course of reading and study must form the divine, the physician, and the practical professor of the laws; but every man of superior fortune thinks himself born a legislator.

Yet [Cicero] was of a different opinion: “It is necessary,” says he, “for a [Roman] senator to be thoroughly acquainted with the constitution; and this,” he declares, “is a knowledge of the most extensive nature; a matter of science, of diligence, of reflection; without which no senator can possibly be fit for his office.” (emphasis added).

I’ve not met a legislator who was so prepared. In fact, today it is a virtue that the person seeking office is an “outsider!”

The Consequences to the Public

I will end with Blackstone’s description of what happens when such instruction and knowledge of the “science of law” is lacking among those whom we elect [iii]:

The mischiefs that have arisen to the public from inconsiderate alterations in our laws, are too obvious to be called in question; and how far they have been owing to the defective education of our senators, is a point well worthy the public attention.

Mischief is the consequence. I hope I have done my duty as a citizen and former legislator to bring this to the public attention.

If you would be interested in an on-line course on the “science of law” from a Biblically informed understanding, please let me know.

[i] Civil liberty is the right to do “what the law permits.” The ignorant of today think it means the law must let them do what they want. That is why liberals hate our common law foundations and the episodic Supreme Court decisions that rest on them.

[ii] The etymology of the word “clerk’ used in government today, e.g. “law clerk” or “Clerk of Court” drives home the close relation between law and the clergy that once existed. “c. 1200, ‘man ordained in the ministry, a priest, an ecclesiastic,’ from Old English cleric and Old French clerc ‘clergyman, priest; scholar, student,’ both from Church Latin clericus ‘a priest,’ noun use of adjective meaning ‘priestly, belonging to the clerus’.”

[iii] Some think they would qualify because they went to law school. I am proof a legal education is not sufficient to qualify as a statesman. For example, most, like me, think common law is judge made law, because that is what most law students have been taught for over 80 years. That belief is a modern innovation arising from an evolutionary worldview, not a Christian one.

David Fowler served in the Tennessee state Senate for 12 years before joining FACT as President in 2006.