What I Gleaned From the Governor’s Call to Prayer and Fasting

Oct 11, 2019 by David Fowler

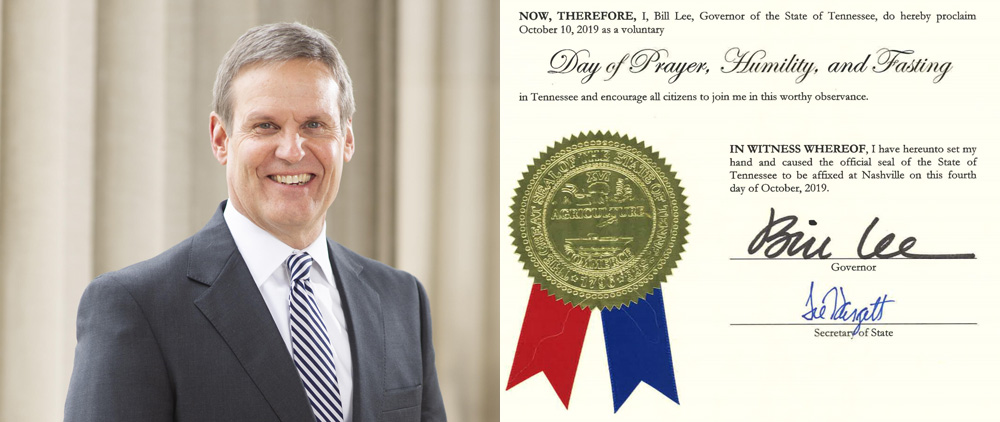

Earlier this week Governor Lee issued a proclamation for October 10th urging citizens to engage in a day of prayer and fasting. A big event relative to the proclamation was scheduled for the large civic auditorium in Nashville. Some greeted it with enthusiasm and great approbation. Others greeted it with great objection. While I appreciated his proclamation, I took the objections seriously and found myself very convicted in a surprising sort of way.

As I read some of the media stories and social media comments, it seemed to me that the objections tended to fall into one of three categories. The first was that the governor’s language about prayer and the reasons for praying spoke in terms of “we,” meaning all the people of Tennessee. The second, ironically, was that inviting everyone to participate who wanted to was not inclusive. The third was that the proclamation was either a slippery slope toward an unconstitutional establishment of religion or was, in fact, an establishment of religion.

As to the first objection, if imputing to all Tennesseans beliefs about prayer and reasons for prayer was really the issue, it would seem that the governor could cure that the next time, if there is a next time, by saying only what he believes. Then, it would be clear that he was speaking only for himself and would be speaking only to those who believe what he believes.

I say that, of course, tongue in cheek, because the real problem wasn’t that he spoke of prayer and fasting in terms of “we,” but, as will be demonstrated, that he spoke to the matter in the first place.

As to the second objection, a government official can’t speak about prayer and fasting without someone—those who don’t believe in prayer and fasting—feeling excluded, which is a bit ironic because I suspect many of those who objected on this ground were complaining about being excluded from that which they don’t believe in doing in the first place.

But the larger point is this: If a government official can’t speak about doing that which some want to do without violating the “rights” of those who don’t want to do that or who don’t believe in doing that, then a government official can’t speak at all about doing or not doing anything.

There will never be complete unanimity among all the “we’s” in Tennessee on anything Tennessee and Tennesseans should do. So, again, the real issue is what he spoke about—religion.

So, it seems to me, when we boil it down, the real problem is that governor spoke about religious matters. The first two objections were just a way for opponents to avoid saying from the get-go that they object to any relationship between religion and civil government.

In polite society, particularly down South, folks don’t want to come right out and say atheism should be the guiding principle for civil government.

Of course, that concept is at the core of the name given to the organization called Freedom from Religion Foundation, one of the primary objectors to the proclamation. However, if the organization meant what its name implies, it would close down, because its sole mission is to speak to the relationship between religion and civil government. That’s entanglement in religious matters, not neutrality.

No religious person should ever let an organization whose mission is self-referentially defeating dictate what should be done. Every threatening letter from that organization should receive a short, written reply: “When you figure out how speaking about keeping religion out of government is not based on your religious beliefs, your beliefs about God, and the relationship between God and government, then come see me.”

Of course, we’ve been trained not to see the connection between atheism and theism, even though “theism” is the root of the word “atheism.” But theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper got it right when he wrote, “Every general development form of life must find its starting point in a peculiar interpretation of our relation to God.”1

Having said that, he then turned to this question from those who embraced “Modernism,” his word for the belief there is no God: “How then do you explain the fact that Modernism also has led to such a general conception [of a form of life or way of living], notwithstanding it sprang from the French Revolution, which on principle broke with all religion?” (emphasis supplied)

Here was his answer:

As stated previously, what many in our nation demand is a civil government and the laws it enacts be founded on and guided by atheism. What’s sad is that many Christians, in practice, agree with them, though they would vehemently deny it.

But consider how reticent Christians—and I include myself— have been over the years, especially now, to justify the policy positions they hold on their belief that a Creator God has laid down immutable laws by which the ethical principles undergirding every civil law can be evaluated for their justice and rightness.

As I reflected Thursday (when I wrote this) on my own experience in this regard, I realized I had not been forthright at times when challenged about a policy position. I could have kindly but forthrightly said something like this: “Because all policy positions are based on ethical considerations and because all ethical considerations proceed from a viewpoint that makes some judgment in regard to God, I will be happy to offer my own religiously-grounded thoughts for consideration among those of all the others who are offering theirs.”

That I have not always been willing to do something like that and what that says about my own heart toward the God in whom I profess to believe was the focus of my prayers on Thursday. And the early returns on God’s answer to those prayers were very convicting. It’s hard to say I’m not ashamed of the gospel when I want to leave out the very God behind the gospel.

NOTES

1. Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism: Six Lectures Delivered at Princeton University, Under Auspices of the L. P. Stone Foundation (1898).

David Fowler served in the Tennessee state Senate for 12 years before joining FACT as President in 2006.

As I read some of the media stories and social media comments, it seemed to me that the objections tended to fall into one of three categories. The first was that the governor’s language about prayer and the reasons for praying spoke in terms of “we,” meaning all the people of Tennessee. The second, ironically, was that inviting everyone to participate who wanted to was not inclusive. The third was that the proclamation was either a slippery slope toward an unconstitutional establishment of religion or was, in fact, an establishment of religion.

Answering the First Objection, ‘We’ the Tennessee People

As to the first objection, if imputing to all Tennesseans beliefs about prayer and reasons for prayer was really the issue, it would seem that the governor could cure that the next time, if there is a next time, by saying only what he believes. Then, it would be clear that he was speaking only for himself and would be speaking only to those who believe what he believes.

I say that, of course, tongue in cheek, because the real problem wasn’t that he spoke of prayer and fasting in terms of “we,” but, as will be demonstrated, that he spoke to the matter in the first place.

Answering the Second Objection, Not Inclusive

As to the second objection, a government official can’t speak about prayer and fasting without someone—those who don’t believe in prayer and fasting—feeling excluded, which is a bit ironic because I suspect many of those who objected on this ground were complaining about being excluded from that which they don’t believe in doing in the first place.

But the larger point is this: If a government official can’t speak about doing that which some want to do without violating the “rights” of those who don’t want to do that or who don’t believe in doing that, then a government official can’t speak at all about doing or not doing anything.

There will never be complete unanimity among all the “we’s” in Tennessee on anything Tennessee and Tennesseans should do. So, again, the real issue is what he spoke about—religion.

Answering the Third (and Real) Objection, Establishment of Religion

So, it seems to me, when we boil it down, the real problem is that governor spoke about religious matters. The first two objections were just a way for opponents to avoid saying from the get-go that they object to any relationship between religion and civil government.

In polite society, particularly down South, folks don’t want to come right out and say atheism should be the guiding principle for civil government.

Of course, that concept is at the core of the name given to the organization called Freedom from Religion Foundation, one of the primary objectors to the proclamation. However, if the organization meant what its name implies, it would close down, because its sole mission is to speak to the relationship between religion and civil government. That’s entanglement in religious matters, not neutrality.

No religious person should ever let an organization whose mission is self-referentially defeating dictate what should be done. Every threatening letter from that organization should receive a short, written reply: “When you figure out how speaking about keeping religion out of government is not based on your religious beliefs, your beliefs about God, and the relationship between God and government, then come see me.”

How Atheism Is Religious in Nature

Of course, we’ve been trained not to see the connection between atheism and theism, even though “theism” is the root of the word “atheism.” But theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper got it right when he wrote, “Every general development form of life must find its starting point in a peculiar interpretation of our relation to God.”1

Having said that, he then turned to this question from those who embraced “Modernism,” his word for the belief there is no God: “How then do you explain the fact that Modernism also has led to such a general conception [of a form of life or way of living], notwithstanding it sprang from the French Revolution, which on principle broke with all religion?” (emphasis supplied)

Here was his answer:

The question answers itself. If you exclude from your conceptions all reckoning with the Living God just as is implied in the cry, ‘no God no master,’ you certainly bring to the front a sharply defined interpretation of your own for our relation to God. (emphasis supplied)

The Foundation for Civil Government and Its Laws

As stated previously, what many in our nation demand is a civil government and the laws it enacts be founded on and guided by atheism. What’s sad is that many Christians, in practice, agree with them, though they would vehemently deny it.

But consider how reticent Christians—and I include myself— have been over the years, especially now, to justify the policy positions they hold on their belief that a Creator God has laid down immutable laws by which the ethical principles undergirding every civil law can be evaluated for their justice and rightness.

Taking These Thoughts to (My) Heart

As I reflected Thursday (when I wrote this) on my own experience in this regard, I realized I had not been forthright at times when challenged about a policy position. I could have kindly but forthrightly said something like this: “Because all policy positions are based on ethical considerations and because all ethical considerations proceed from a viewpoint that makes some judgment in regard to God, I will be happy to offer my own religiously-grounded thoughts for consideration among those of all the others who are offering theirs.”

That I have not always been willing to do something like that and what that says about my own heart toward the God in whom I profess to believe was the focus of my prayers on Thursday. And the early returns on God’s answer to those prayers were very convicting. It’s hard to say I’m not ashamed of the gospel when I want to leave out the very God behind the gospel.

NOTES

1. Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism: Six Lectures Delivered at Princeton University, Under Auspices of the L. P. Stone Foundation (1898).

David Fowler served in the Tennessee state Senate for 12 years before joining FACT as President in 2006.